The Curse of Plenty

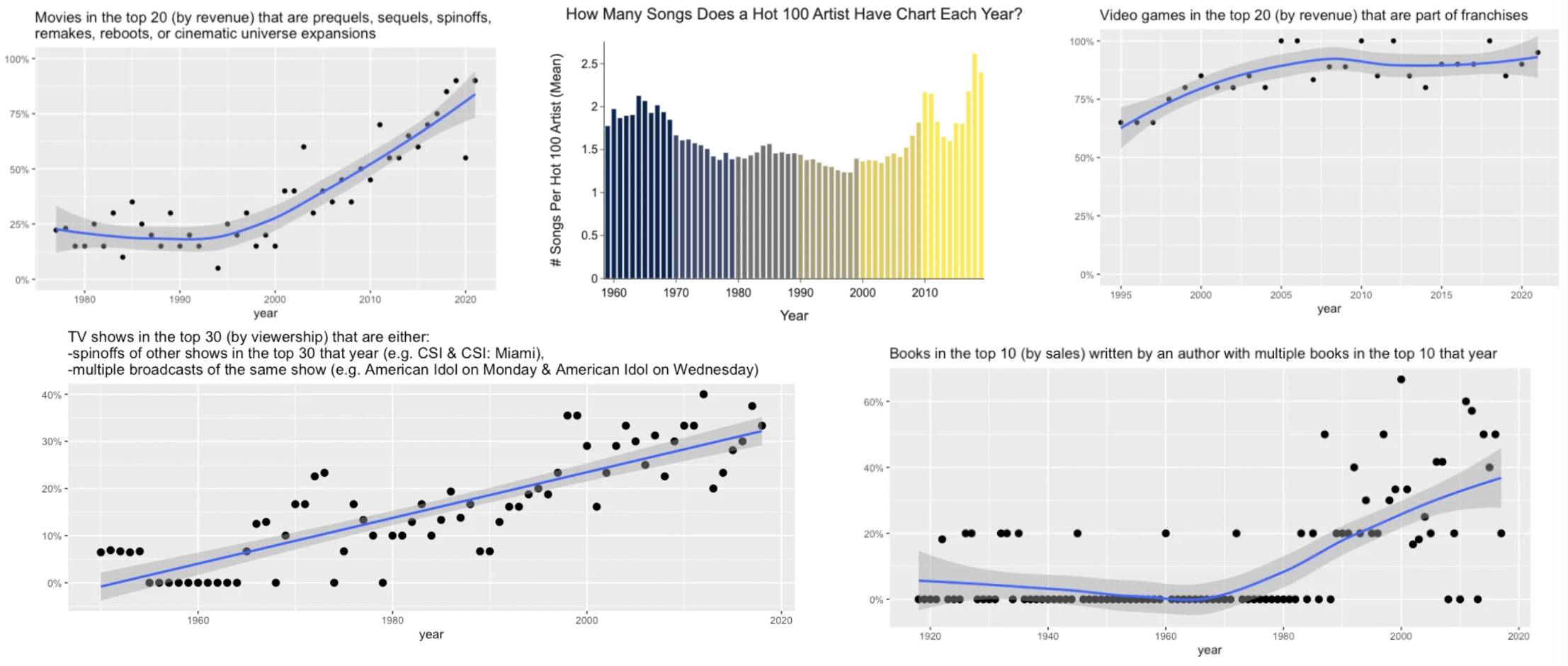

An interesting newsletter by Adam Mastroianni pulls together data from movies, television, music, books, and video games to show that in each of these domains, the biggest hits dominate an increasing share of revenues, and are themselves increasingly dominated by franchises. Here are a few representative charts that Mastroianni put together:

A lot has been written about how franchises dominate the box office today, and some have used this to argue that progress in culture (or at least some forms of culture) has stalled out. Seeming to bear out that conclusion, Mastroianni’s post showed this problem extends to pop culture in general.

But in fact, this problem goes beyond pop culture too.

A 2021 paper by James Evans and Johan Chu titled Slowed Canonical Progress in Large Fields of Science shows that, in science, top papers garner more and more citations, turnover of top papers has slowed, and everyone cites the same papers (academic franchises?). In other words, science seems beset by similar problems as pop culture. Fortunately, Evans and Chu’s paper sketches out a model of why this happens, and I think their explanation can be extended to pop culture as well.

The heart of their explanation has to do with the total quantity of scientific papers, which has expanded enormously over the last 100 years. In the figure below, each point represents a field in a given year. In the left figure, on the vertical axis we have citation inequality. In the right figure, it’s correlation across years of the ranking of the top 50 most cited articles, by field. In each figure, on the horizontal axis is the size of the field (# of papers/yr).

These figures show bigger fields have more inequality and more ossification of top cited papers.

Mastroianni’s newsletter plots trends related to franchises and concentration against time, but we know from the work of people like Joel Waldfogel that the number of books, movies, songs, and TV shows has gone way way up over time (I assume the same for video games, but Waldfogel doesn’t look at that).

I suspect that if you re-plotted Mastroianni’s figures so that the horizontal axis was the number of new works per year, you would get an even tighter relationship. In other words, in any field of content production, whether it’s scientific journal articles, movies, music, TV, books, or video games, as the number of new works per year increases, the most popular stuff garners an increasingly large share of the audience, and is increasingly composed of franchise-like content.

Why?

Dynamics of Attention

I think the key idea across these domains is network effects; the value of a work is higher when it has a larger audience. If you’re a scientist, you want to work on research related to what other people are working on; similarly, you want to communally experience art with other people. To take advantage of network effects, it is necessary for the audience to coordinate on what to give limited attention.

Evans and Chu, talking specifically about scientific papers, argue that when the flow of new papers is small, people can sample very broadly and form judgements which are shared and debated; over time, a consensus about which papers are best can gradually emerge.

But when scientific fields get too big, this dynamic no longer works. There are two problems. First, in a big field it takes longer for people to arrive at a consensus if they are each independently sampling over an increasingly small share of all the papers. It just becomes less and less likely two people have read the same paper and can build a consensus around it. Second, even while this process takes longer to play out, it is disrupted at a faster rate by the inflow of new original works. People lose interest in hashing out the merits of older papers and move onto the new thing. As evidence of this dynamic, note the increasing correlation of the rankings of the top 50 papers, as fields get bigger. It gets increasingly rare for new papers to dethrone older champions.

And when that does happen, it follows a different dynamic than this gradual process of consensus building via independent assessment and discussion. Instead, as fields get bigger, the hits achieve their success via some kind of viral channel that focuses a lot of attention quickly on the paper (a favorable writeup in the NYTimes? A big-name author? Twitter vitality?).

The figure below is the median time until a paper enters the top 0.1% most cited (vertical axis) against the size of the field (horizontal). Note small fields can slowly build up steam, and take a long time to reach top 0.1%. But in big fields, it’s more like instant fame or bust. You either make a splash instantly or people move on to the next thing.

I suspect the same dynamics underlie the pathologies in pop culture. When a domain is small, high quality can be identified by a similar process of consensus building via independent sampling. But when a domain gets big, audiences become too fragmented for that approach to work well. Just as scientists lose interest in hashing out the merits of older papers and move onto the next thing, so too do pop culture audiences lose interest in disputed art of the past (which few of their friends have seen anyway) and move on to something new.

That also means, as a field grows, the best strategy for a commercial art producer changes. When a field is small, it may be a viable strategy to simply make the highest quality (mass appeal) art possible, and then count on enough people to see it and convince others to do likewise. A consensus about it’s quality will emerge.

But when a field is large and crowded, that strategy may no longer be viable. With few exceptions, the only art that can benefit from network effects is art that quickly captures a large share of audience attention. If that art happens to be high quality, then the audience will identify it and you’ll have a big hit. But even if it’s not, if the network effects are strong enough, people might settle for mediocre work that they can enjoy communally.

To capture audience attention, you need to finance art that is capable of sending powerful signals to the audience, to coordinate their attention prior to release. One of the best ways to do that is to build franchises; in that setting, the quality of prior art is a credible signal of the quality of new art.

If you believe franchises tend to be lower quality than the best original stuff, then in the past, this franchise-based strategy would have been worse than one that only focused on producing the highest quality stuff. That’s because, in the past, the smaller number of new products would have meant the highest quality stuff would eventually be identified and attract more attention than comparatively mediocre franchise offerings. But that’s no longer the world we live in.

So it’s not that we’re running out of ideas; we have more than ever! But that very fact is also a curse that means the most popular stuff looks less and less creative. It has to look like what’s come before, in order to win the war for attention in an environment of superabundant choice.

Adapted and extended from a twitter thread on this topic.

Rick Rubin noticing the same problem in this Conversations with Tyler, on older vs. newer music in the era of streaming.

This is great, I feel like I finally have a mental model for understanding why movies are all franchises and reboots now!

Adam Mastroianni’s original post—and my previous take on this phenomenon—were pretty pessimistic about the state of creativity in our culture. But, for me anyway, understanding what’s happening through the lens of this mental model restores a lot of optimism. The big takeaway for me is that looking at the creativity of the top performing works in a field isn’t a good way to assess the creativity of the whole field.

When we see yet another big franchise installment or reboot topping the charts, it isn’t because the producers have just run out of ideas or are too risk averse to make good original art. The good art is still being produced, and more people than ever are able to access it. It just gets eclipsed (somewhat mechanically) by the huge network effects driving people to also consume the familiar franchises.

I see this most clearly in TV shows. Breaking Bad, Mad Men, Game of Thrones, etc. may not beat out American Idol and NCIS in the ratings, but they’re still out there for tons of people to enjoy. And I would bet that a lot of people watch both the critically acclaimed original TV shows and the less creative franchises, for slightly different reasons. One more to enjoy the art itself and to talk about with a more close-knit community, the other for the wider communal experience (plus sometimes you just want to zone out and not pay as much attention to the TV anyway).

I think this argument may apply to science as well, though this is less clear to me. I could see, for example, scientists citing an older, fundamental paper just to acknowledge the intellectual landscape they’re operating in, while also citing newer, more creative work that is more relevant to their own work. This process would lead to the ossification of the top citations that you point out, without necessarily being a mark against the creativity of the field.

Thanks! I think there is also a pessimistic read, which is that these dynamics affect the direction of cultural creation; specifically, commercial creators will be pulled towards doing franchise-like work for anything expensive. Original and outlier work will have to happen on smaller budgets, where a smaller return can justify the investment. Whereas we used to get “expensive + original”, now we’ll probably have to content ourselves with “cheap + original.”

That’s a good point. It seems potentially relevant that TV seems to have been most exempt from this trend (with all the “Golden Age of TV” discourse over the last decade or so), and TV is probably the one medium where financial results are furthest downstream from the production itself. There’s a lot tighter feedback loop between a movie’s popularity and its profitability than there is with a TV show. Maybe there’s a lesson in there for how to promote creativity in other domains, but I’m not sure.

Related, an interview with David Ellison, producer of Top Gun: Maverick:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-05-30/-top-gun-maverick-producer-on-tom-cruise-netflix-and-the-future-of-movies

More evidence that, until quite recently, it paid to make a good movie to get a big audience, but that’s no longer the case. For several years, critics ratings for the top ten movies have steadily diverged from audience ratings. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-08-28/critics-and-fans-have-never-disagreed-more-about-movies

Very interesting.

Re movie franchises and cinematic universes, I see it as a branding issue analogous to food/beverage chains. If I see a Starbucks, I know what to expect, I know whether or not it’s the kind of thing I like, and I can count on a certain level of quality. A boutique coffee shop might be better than Starbucks, but I’m taking a chance.

Similarly, if I go to see a Marvel movie, I know what to expect, etc. Whereas if I see some other movie, even if I know it’s in the action/adventure or superhero genre, I’m taking more of a chance.

The only thing that I wonder is why it took the movie studios so long to figure out that when they have a winner, they should keep milking it. There are some examples in the past, such as the James Bond series, but it seems much more of a known strategy now. (Like, after the first wildly successful Star Wars trilogy, it took 15+ years to make another one. And I don’t think there were any movies outside the main story line until Disney took over.)

Not that this contradicts any of your analysis; in fact I think it dovetails with what you’ve said here.

Agree that franchises are fundamentally about branding!

But I think it’s not just that it took movie studios a long time to learn that branding was effective. I think the strategy only became very effective in the new environment where there were lots of choices for consumers. One way to think of it is to assume that consumers rely on two pieces of information when making a judgment about which movie they will most enjoy: word-of-mouth and similarity to other movies they’ve seen and enjoyed.

When the number of movies is small, enough people see every movie that word-of-mouth is a very reliable guide to the quality of a movie. Here, I’m thinking word-of-mouth is from people you already know well, and so you can judge their taste. Like in a small town, everyone knows the artisanal coffee shop, and so Starbucks isn’t desirable. But when the number of movies is really large, word-of-mouth is not very reliable. You never know more than one or two people who have seen any movie, and even fewer who have seen more than one that you’re choosing between.

In the latter environment, you start to give more weight to the similarity of a movie to other movies you’ve seen. And that creates a feedback loop, because if more people start choosing to go to movies based on their similarity to other movies, then you can only get accurate word-of-mouth information about those kinds of movies (franchises). In the second environment, it starts to pay more to make movies that are similar to existing movies, even if they not be as good as the best original movies. In the second equilibrium, the problem is that the really good original movies can’t be identified, and so they languish at the box office.