The Engine of Progress: Why Growth Matters

Link post for The Engine of Progress: Why Growth Matters on Substack.

Economic growth is much more important and consequential than you might think

Introduction

Growth is probably the most important concept in the world. But it isn’t intuitive that economic growth is both desirable and possible over the long term.

For most humans throughout history, life has been overshadowed by resource scarcity and the sudden threat of death due to famine, injury, or violence[1]. The story of progress—how we have improved our material and societal well-being—is a story of economic growth (broadly defined) driven by technology, cooperation, the harnessing of energy, and an increasing human population.

Growth is, as I’ll argue, not just an obsession of greedy capitalists and politicians, nor is it just an academic exercise for economists. Economic growth has enabled more or less everything we value about modern society, directly or indirectly.

To create a better world for everyone – and to keep improving it indefinitely – we must continue to grow. The importance of continued growth isn’t intuitive, but it is essential to sustain and enhance our well-being. Long-term growth isn’t just a matter of material abundance and flying cars; we need to grow to secure the continued existence of prosperous and peaceful societies and eliminate poverty and scarcity where they still exist. A world without growth is one where we all fight for the same limited piece of the pie.

What is growth?

Economic growth is, in plain terms, the increase in the quality or amount of products produced by an economy, typically measured on a yearly basis by looking at Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[2]

In traditional or classical economics, growth was thought to result mainly from combining capital and labor. In other words, by combining “things” like resources, money, and energy with human effort, we’d expect the economy to grow proportionately to the total amount of capital and labor.[3]

To make things more concrete, imagine the economy as a simple factory with workers (labor) and machines (capital) that produce a given amount of output every year. If you double the number of workers but keep the number of machines constant, the workers’ productivity is limited by the amount of machines available. If you double the number of machines but keep the workers constant, many workers will be left idle and unproductive. Only when you grow the number of workers and machines in tandem can you grow the factory’s productivity—and output—proportionally.

Before the Industrial Revolution, the economy grew slowly and only when there was sufficient capital and labor. Otherwise, a surplus of labor or capital would lead to stagnation or shrinkage. This was known as the Malthusian Trap. At pretty regular intervals, the human population became unsustainably large given the level of resources available and subsequently stagnated or shrank (because of famine, disease, etc.).

At the turn of the 19th century, the economist Malthus predicted that we would be caught in this trap in perpetuity. Instead, the Industrial Revolution sparked an economic productivity boom that helped us collectively escape it. What was it about the Industrial Revolution that changed the nature of economic growth?

The answer is innovation through the diffusion of new ideas and technology.

In our factory analogy, better technology enables the factory to invest in new machines, improving automation. New organizational improvements can organize people better and improve operational efficiency. Neither of these kinds of improvements are strictly about adding more capital or labor but about improving their productivity.

Post the Industrial Revolution, when economists measure productivity growth, they find that the output of an economy is often greater than expected based on the pure inputs (of capital and labor). That is, when trying to account for all the inputs that drive economic output, there remains a set of unexplained factors that contribute to the total measure of growth. The difference is mainly believed to be made up of the multiplicative effect that technology and ideas have on capital and labor productivity. This “residual” factor of productivity growth is referred to as Total Factor Productivity (TFP) and is essentially the result of innovation.[4]

In other words, innovation is like magic pixie dust for the economy and creates more growth than can be accounted for by the raw inputs. It represents the efficiency gains in the economy, often driven by technological, organizational, or operational improvements. It covers everything from better agriculture machines (tech) to adopting agile software development methodologies (ideas) to brand-new inventions from research—and their diffusion throughout the economy.

Ideas are the fuel that powers growth

The right ideas lead to processes or technology that make everything more efficient. These productivity gains allow an economy to produce more output with the same inputs, increasing economic growth. Without TFP growth, an economy grows solely by adding more capital or labor and will eventually get diminishing marginal returns.

This is why TFP growth based on innovation plays a crucial role in the growth of developed economies. It enables a productivity growth loop where new ideas and technology lead to better ways of doing things that allow us to use more capital for any given amount of labor, leading to more economic growth, which sustains a larger population that can generate more new ideas, and so on.

Due to the nature of economic growth, our modern world is one where a growing population becomes a crucial input to facilitating further growth rather than a burden; the more people there are, the more ideas they have.

What happens if we stop growing?

The absence of growth leads to zero-sum competition for a limited set of resources.

Growth is essential not because of some cartoonish idea of greed but because continued growth is the only way to escape the Malthusian trap. The only way to avoid a world of perpetual poverty and violent competition where one person’s gain is another’s loss. Where theft and plunder is the best way to get rich.

Pretty much everything we want and value in the world is downstream of a higher standard of living, itself a result of economic growth. This may strike many as an overly materialistic or reductionist view. To be sure, there’s more to the good life than GDP growth, but as it turns out, it correlates pretty well with many things we care about, including intangibles like happiness. Richer countries (and societies) are generally happier, freer, and more pleasant places to live.[5]

“Productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”

- Paul Krugman

A world in which the pie grows a little bit every year is one in which nations and people can afford to be more future-oriented and altruistic. A world in which the pie is constant, or shrinking, is one in which people will inevitably compete for the same limited amount of resources and be more concerned with their security and in keeping what they have. The circle of empathy will tend to get smaller and smaller. This is the world people have lived in throughout human history, and it’s not a great world for most of us. Or, to paraphrase Yoda:

Growth makes most problems more solvable, whereas a lack of growth exacerbates them. Unfortunately, ideology blinds us to this. Conservatives care a lot about things like national identity, traditional values, cultural preservation, and immigration restrictions. Progressives focus on inequality, environmentalism, redistribution of wealth, identity politics, etc. In the discourse around such topics, it’s easy to lose sight of the underlying engine that powers a nation’s prosperity: namely, economic growth. While cultural preservation, the environment, identity, and equality are very important topics, people too often neglect the critical role of growth as the more fundamental concern.

A growing economy can afford to invest in education, healthcare, infrastructure, and other public goods that contribute to the overall well-being of the nation’s citizens. It also comes with higher rates of employment and provides its people with opportunities for upward mobility, fostering a sense of hope and optimism about the future. This, in turn, contributes to social stability and cohesion, which are essential for preserving cultural values and reducing inequality. For example, the post-WWII economic boom in the US paved the way for the civil rights revolution and subsequent legislation and reforms.

On the other hand, when economic growth stalls or reverses, the opposite happens. Job losses and economic insecurity can stoke fear and resentment, leading to social and political unrest. This can manifest in various ways, such as anti-immigration sentiment, mercantilism, increasing polarization, and a retreat into national, ethnic, and religious identities, all of which are typically seized upon by populists. While there are many reasons for the rise of populist movements during the last decade, it’s hard to deny the largely negative impact of the 2008 financial crisis and the secular stagnation of the last few decades.

This is not to say that economic growth is a panacea for all social and political ills or that cultural and identity issues are unimportant. Instead, it’s a reminder that a prosperous and stable society requires a solid economic foundation. Economic growth enables progress, making everyone better off.

Is infinite growth possible in a finite world?

In his misguided quest for balance, the supervillain Thanos from the Marvel Universe believed that the resources of the universe are finite and that by killing half of all life, he could prevent life from eventually destroying itself. This conclusion feels harsh but true to many people, which is why Thanos is such a believable villain. He is, however—like all Malthusians—fundamentally wrong about the nature of the universe and its seeming finiteness.

While it is true that Earth only has a limited set of raw materials and finite space for people to live on, in practice, fears of overpopulation or running out of resources are much overblown. First, there have been countless predictions that the world will run out of all manner of resources like farmland, fertilizers, coal, and oil. None of them have come true. Second, fears of overpopulation leading to famine have similarly been predicted multiple times but failed to materialize.

In fact, the opposite has happened; thanks to the miracle of economic growth driven by technological innovation, we have broken out of the Malthusian trap and have been able to sustain a growing population due in no small part to things like greatly improved agricultural practices, the transitioning away from resources we are running out of, and increasingly abundant energy.

Natural resources don’t limit growth because, over the long term, growth is mainly driven by technological innovation or, in other words, new ideas. Ideas about how things work, or in other words, knowledge, are what turn iron ore in the ground into usable steel and steel into skyscrapers. Ideas are a kind of resource, but it’s a resource we never run out of, quite the opposite. Compared to regular resources, an idea “consumed” by one person won’t prevent someone else from using that idea. Instead, ideas tend to spread.

Resources and the environment

It feels deeply counter-intuitive that we aren’t limited by physical resources. How is this not the case? And besides, isn’t our rapid extraction of raw materials and increasing pollution causing real harm to the environment?

Historically, it’s true that economic growth has often resulted in greater environmental harm and pollution.[6] But as it turns out, when countries develop and industrialize, their environmental footprint eventually gets smaller, at least per capita – they get more from less.[7]

How is this possible? Innovation enables us to do the same things more efficiently and unlock new ways of doing things. In addition, economic growth steadily dematerializes as economies become more advanced. Growth increasingly comes not just from using more resources but also from services and other intangibles like digital content, the ability for remote work, cloud computing, and so on.

People in developed countries also tend to care more about the world outside their immediate surroundings, valuing the preservation of animals, a sustainable climate, less poverty, and so on. They recycle, reuse, and pollute less. When you’ve climbed all the way up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, you can afford to worry more about the future of humanity and not just about putting food on the table.

But what if every country eventually becomes a “developed” country, wouldn’t that consume all our resources and devastate the planet, even if they all adopt renewable energy? As it turns out, not only is the ongoing energy transition expected to require us to extract fewer total resources than what we are using today, but crucially, demand for more energy or resources drives innovation itself. This leads to new technology that offers the same benefits with less or entirely different raw materials. As I noted above, when a given resource becomes scarce, we tend to transition away from that resource to something else. The history of technology has demonstrated this over and over again.

For example, during the 19th century, manure (a.k.a shit) was used as the primary source of fertilizer, and a quickly growing population required more and more of it to the point that by the latter part of the century, the world was literally running out of shit. This urgency forced governments to find alternate sources of fertilizers, so scientists invented artificial fertilizers instead. Another example is when we were hunting whales for whale oil during the 19th century, but high demand and rising prices spurred the development of alternatives, including kerosene, which was cheaper, more efficient, and didn’t involve hunting whales to near extinction. Yet another example looks to be taking place now when many claim we won’t have enough lithium for all the batteries we will need. Neglecting the fact that there is still plenty of lithium on earth to cover our needs for the foreseeable future. A similar story is playing out with regard to cobalt, copper, and most other minerals we need for the “green energy transition”.

If we are to learn anything from the history of technology, it is that there are plenty of ways to solve our needs as long as the demand is there. Although individual physical resources or raw materials may be limited in supply, there are an infinite amount of ideas. We just need the right knowledge and the will to apply it.

Does economic growth increase inequality?

What about wealth inequality, doesn’t economic growth create more of it? Doesn’t it just exacerbate the gaps that already exist?

The paradox is that it can increase income and wealth inequality, at least in the short term, but benefits everyone in the long term.

Economies grow because some people and companies invent things that make it possible to do other things better and faster. Those people usually get very well compensated for what they create, typically because they own equity in a company (although the value they capture tends to be far less than the total value they create).[8]

Nevertheless, almost everyone in the economy benefits from the overall increase in wealth and material progress generated from growth, even though everyone’s wealth doesn’t increase as fast. One reason for this is that the same amount of money in inflation-adjusted terms will get you much more today than in the past (for most goods and services). Even relatively poor people today have access to many products and services that rich people hundreds of years ago couldn’t even imagine. It is a tide that lifts all boats.

Most economists would agree that economic growth increases inequality (although there are considerable disagreements about how much). Taxation and income redistribution probably helps on the margin but doesn’t solve the underlying problem. The question is, what’s the alternative? The alternative is that everyone is equally poor, which is not what most of us would want. A world without growth is a worse world for most people most of the time.

What about the very long term? Won’t economic growth eventually lead to extreme inequality?

Dystopian capitalist narratives of the future imagine a world with absolute wealth inequality, like a medieval feudal society, but with advanced technology and global corporations controlling everything. A tiny fraction of people have all the wealth, and the rest of us have nothing. “Best case,” we get to live in virtual reality or are constantly sedated with narcotics; worst case, we live in cyberpunk slums while the elite take space cruises to Mars.

Compelling but fantastical narratives like these are a far cry from reality. Inequality has increased and decreased as wealth has been destroyed and created throughout history. We can expect similar things to happen in the future. If anything, we want to continue growing to ensure that democratic, peaceful, and free societies continue to exist. Even imperfect and unequal democracies are preferable to totalitarian alternatives where “everyone is equal” (but some are more equal than others).

That being said, though inequality shouldn’t be a problem per se, there are good reasons to curtail the extremes of wealth inequality to some extent. Human psychology is deeply sensitive to issues of fairness. If people feel that someone else’s wealth is “rightfully earned,” then some inequality is okay. But when they think it isn’t, inequality drives a sense of unfairness that can lead to social unrest and divisive politics. In any case, trying to curtail growth to reduce inequality is a bad idea. Instead, there are better ways to deal with the unfair distribution of wealth, like taxing the land instead of labor.

Growth makes most people richer, while a stagnating society surely will make more people worse off.

We need more people, not less

Because ideas are basically infinite, and ideas are the main driver of economic growth in the long run, overpopulation isn’t the civilizational problem it’s made out to be. Rather, in a world where ideas are the fuel of growth, underpopulation becomes the main bottleneck. This is where Thanos and the Malthusians’ reasoning has gone awry.

The more people there are, the more ideas they can have, which in turn enables new technologies to be developed and deployed. A stagnating or shrinking population risks putting a halt to the economic growth loop.[9]

This is why it’s so worrying that humanity faces a stark and consistent fertility decline; the average number of children born per woman across the world is now close to replacement levels of 2.1. Most developed countries are already far below that.

Although the world population will continue to grow for a few more decades – mainly in African countries – demographers predict that it will peak before the end of the century at around 10-11 billion people and then start to decline. Humans are unlikely to go extinct, but a continuously decreasing population will, in the worst case, lead to perpetual economic deceleration, with social and political unrest, more conflict, and a worse world for everyone. “Best case,” human populations rebound but our current civilization will essentially disappear and be replaced by people with much more tribal and traditional values that promote higher fertility.

In the short term, we can probably do many things with the people we have to continue innovating. For example, governments should be spending even more on R&D; we should consider targeted deregulation to spur more innovation across various industries (like nuclear!) and continue having the developing world “catch up” to bring more and more people out of poverty, so even more of us can contribute to the human idea machine. In the long term, AI (artificial intelligence) can play a role both as an idea-generator and through increased automation of the economy. It’s unclear what the long-term effects on employment and labor would be, but it’s not a given that everyone will be out of a job or that we will even need to work all that much in the first place (maybe we will have a lot more time to spend with our kids).

To get more people to have kids, developed nations need a more pro-natalist culture that encourages men and women to have more kids earlier. This is a tall order, however, given that such pro-natalist values will often come into conflict with other modern values around individualism, liberalism, and feminism. So developed countries can at least provide generous paid parental leave and childcare services, whether privately or government-funded. We might even want to pay people hundreds of thousands of dollars to have kids (we can afford it!).

Contemporary society is largely unaware of how important population growth is for our future prosperity. Like Thanos, we are Malthusians by default and see overpopulation and overuse of resources as our greatest threat rather than as problems we can solve or perhaps even as parts of the solution itself.

Growth and energy

Thanks in part to the dematerialization of economic growth and a drive for efficiency, developed countries have been able to decouple economic growth from increased energy usage.

This is good because it means that we now know we can grow without risking the complete collapse of the natural environment or catastrophic global warming. Better energy technology, new kinds of renewable energy sources, and even non-renewable but less-polluting energy sources like natural gas all play a role in this transition.

Nevertheless, I think that we actually need to increase energy usage to continue growing over the long term.

In a previous article on growth and energy consumption, I shared the chart below of the so-called “Henry Adams curve.” I wrote that declining growth rates and technological stagnation since the 70s correlate well with flatlining energy use per capita:

The story of human progress is largely a story of how much energy we have been able to harness and put to productive use. Starting with our early ancestor’s ability to harness fire to the discovery that we could split the atom, and beyond.

Declining energy usage is therefore a problem because technological innovation and growth are tightly correlated with increased energy consumption, and technological innovation is one of the main drivers of progress. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that in order to drive innovation broadly, we have to use more energy because advanced technologies are generally more energy-intensive. All things equal, increased energy efficiency is great, but all things aren’t equal and we’ve traded growth for efficiency.

While most people erroneously believe that using less energy overall is desirable, and hardcore environmentalists even consider it to be immoral, using more energy rather than less is perhaps the only way we can ensure growth over the long term. Using more energy is not necessarily the same as polluting and releasing CO2 (although we will likely have to do more of that for some time). We can produce energy more cheaply and with less and less impact on the climate. Many problems that stem from industrialization are perhaps best solved by figuring out how to produce and use much more energy than we can today:

“With enough cheap energy, we could literally pull excess carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and bury it again. Fresh water isn’t actually scarce; it’s a matter of the energy to pull it out of the atmosphere or desalinate ocean water . Energy could make water crises a thing of the past. Orders of magnitude more energy can solve waste problems as well: At high enough temperatures, everything breaks down, so trash and harmful waste problems could disappear. More energy means more fertilizers and more food grown and more construction so it doesn’t even impact land use.”

Making energy much cheaper also means we could afford to do things like travel the solar system and extract raw materials from moons or asteroids.

Eventually, we want to make energy “too cheap to meter.”

Why do people hate the idea of growth?

Humans tend to be very myopic. Exponential growth, feedback loops, and accelerating functions are deeply unintuitive because we evolved in small-scale societies that stayed largely unchanged throughout the extent of our lifetimes.[10] Our current world is full of non-linear, accelerating trends that escape our primitive intuitions.

As I’ve lamented many times over, we are also Malthusians. We imagine the world is like a small life raft that can only fit a given number of people who need to share a limited amount of food. But the world is no longer like that. Instead, economic growth driven by ideas and technology makes overpopulation and overuse of natural resources far less of a concern.

Yet another recurring theme of the human psyche is our bias toward eschatological ideas about the impending apocalypse—whether because of religious dogma or fearmongering, we believe that the end is always nigh. Natural disasters, pandemics, wars, rampant crime, decadent culture; the signs are everywhere! The only way to prevent the end times is to absolve ourselves from our sins. Economic growth and prosperity are such sins, and the only way to save the world is to stop and revert to a simpler way of life.

As a result, many call for us to “degrow” the economy, but such a policy, if enacted, would be devastating. Not only are many countries already dematerializing quickly, but they are also outgrowing their reliance on fossil fuels. Degrowth policies that aim to halt economic growth risk throwing us back into a Malthusian world, condemning most people to poverty indefinitely.

I don’t deny that climate change is a serious problem and will impact some people and regions more than others, but it’s far from an existential threat—we will adapt, and the earth will survive. It would be much worse for us to attempt to reverse growth to “save the environment” than it would be to deal with slightly higher average temperatures but afford to make the whole world much richer and prosperous:

Climate change, in the consensus scientific assessment, is only one of many things that will affect the economy a century hence, and a comparatively small one at that. In numerical terms, “the likely combined direct economic effects [of climate change] could reach 0.7 to 2.4 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product per year by the end of this century.” [117] In other words, a century of climate change in the worst case might cost us as much as liability lawyers do now. And that’s in an economy that is expected to be 5 to 10 times richer than ours is—at the median estimates, climate change might cause our great-grandchildren in 2100 to be 7.38 times richer than we are instead of 7.5 times.

Climate change is a hangnail, not a hangman, for the human race. It’s the equivalent of having a growth rate of 2.53% over the rest of the century instead of 2.551%. Anything, including energy conservation, that reduces the growth rate by a single percentage point will harm our grandchildren 50 times as much as climate change.- J Storrs Hall. Where Is My Flying Car?: A Memoir of Future Past

An alternative to “outgrowing” our environmental problems, as I have suggested above, would be to accept a slower rate of growth for many decades to come. Is it really so bad to grow a little slower? Can’t we just make do with 1% GDP growth compared to 2%? As Tyler Cowen points out, a small difference over a year makes a huge difference over the long term because of compounding returns—or lack thereof:

The importance of the growth rate increases, the further into the future we look. If a country grows at two percent, as opposed to growing at one percent, the difference in welfare in a single year is relatively small. But over time the difference becomes very large. For instance, had America grown one percentage point less per year, between 1870 and 1990, the America of 1990 would be no richer than the Mexico of 1990. At a growth rate of five percent per annum, it takes just over eighty years for a country to move from a per capita income of $500 to a per capita income of $25,000, defining both in terms of constant real dollars. At a growth rate of one percent, such an improvement takes 393 years.

In other words, the only way to “save the environment” and ensure the prosperity and well-being of every current and future human (and other conscious animals) is to grow more, not less.

The long view of growth

I believe that growth is important both objectively and normatively. Objectively, the world IS a better place on the whole when the pie keeps getting bigger for everyone, even with the negative impact of environmental harm in the short term. Normatively, we SHOULD want to keep growing because it’s the best way we know to ensure progress. It creates the kind of world that truly maximizes human potential, gets us out of zero-sum behaviors, and enables the “better angels of our nature” to prevail.

As I’ve repeated over and over again in this article, the crucial input to long-term growth is not mainly resources but innovation (technology + ideas). While technology is as close as we can get to a panacea to most of our worldly problems, technologies aren’t free from negative consequences. The solution to most problems created by technology, however, isn’t less technology but more or new technologies (including things like better policy, markets, and political ideas about how to organize society).

Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin wrote in his excellent piece on techno-optimism, “[…]version N of our civilization’s technology causes a problem, and version N+1 fixes it. However, this does not happen automatically, and requires intentional human effort.“

Technological progress makes it possible to continue growing with a negligible environmental and climate impact. But to get there, economies must first reach escape velocity. Coal and fossil fuels were the unlock required for humans to escape the Malthusian trap. Renewable and carbon-neutral energy is required to advance civilization to the next stage. Luckily, this is already an ongoing process. Solar energy is becoming very cheap, and nuclear power is safe and readily available, so we are more than capable of outgrowing our reliance on fossil fuels.[11]

Even if we keep growing into the hundreds of billions (or trillions!) - perhaps spread out across the solar system—the human population will inevitably start to stagnate at some point in the future. Whether this comes very soon or much later, we might have to rely on Artificial Intelligence to supplement or even replace us as the main drivers of growth. Given recent progress in AI development, it’s not a far-fetched idea to imagine such systems can play this role even in the near future. If we succeed in developing true AGI—and it doesn’t instantly kill us all—it can speed up our innovation process greatly—contributing to continued or even explosive economic growth.

Nonetheless, at some point in the very distant future, the heat death of the universe will put an end to all potential for growth and life. But until then, we are wise to keep trying.

Per aspera, ad astra.

- ^

“The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined” by Steven Pinker. Pinker argues that the rise of modern nation-states, commerce, and organizations has led to declines in violence. While the causes of peace and prosperity are not very well understood, it’s clear that it has something to do with economic/social development.

- ^

According to Wikipedia, “Economic growth can be defined as the increase or improvement in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy in a financial year.”

- ^

As a non-economist, I’ve always found the term “capital” a little confusing as I intuitively take capital to mean simply money. But in economics, the term encompasses a broad range of assets that can be used in the production of goods or services. Physical capital includes tangible assets like machinery and technology for creating goods and services. Human capital involves individuals’ skills, knowledge, and experience, enhanced through education and training, contributing to their value in the workforce. Financial capital refers to the monetary resources used to purchase production tools and equipment. Intellectual capital covers intangible assets such as patents and brand recognition, which are crucial for innovation and growth. Lastly, social capital pertains to social networks and relationships, facilitating effective societal functioning.

Labor, in economic terms, is basically everything that isn’t capital in the equation.

- ^

Productivity growth in an economy refers specifically to the increase in efficiency of converting capital and labor inputs to produce goods and services. Labor Productivity measures how efficiently labor is used in the production process (e.g., output per worker). Total Factor Productivity (TFP) measures the efficiency of all inputs used in production, including labor, capital, but also technology, and everything we can’t exactly measure. It reflects how well an economy combines these inputs to produce output. TFP comes out of the so-called Solow growth model of long-run economic growth.

In reality, economists aren’t entirely sure what TFP really is or comes from. But it’s vital to make countries continue growing after they have exhausted a lot of the low-hanging fruit of capital-fueled growth. See this timely post from econ-blogger Noahpinion for a good overview. - ^

Plenty of research, like the World Happiness Report by the UN, has shown that people in more affluent and developed countries also tend to be happier.

Yes, people were probably quite happy in small hunter-gatherer tribes of close family and friends (when they got some respite from the constant threat of physical trauma, violence, and a brutal environment), but few people with the choice genuinely wish to forgo the convenience and abundance of modern 21st-century lifestyles.

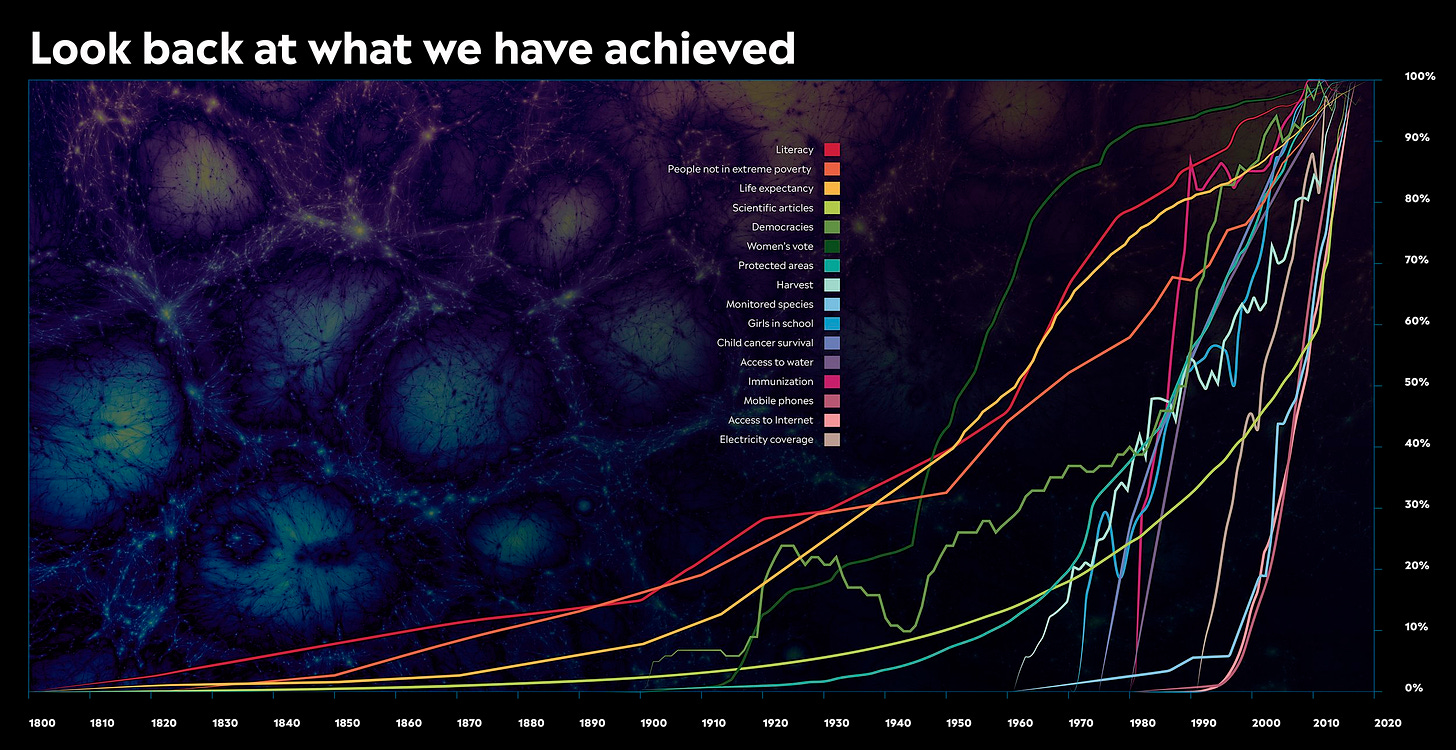

It’s hard to ignore the material achievements of humanity over the past few centuries:Again, from Vitalik’s article. - ^

Humans have always had a detrimental impact on their surrounding environment; in prehistory, we were just too few and far between to make a sustained negative impact on the planet. Well, except for hunting all the mammoths to extinction and probably the Neanderthals as well…

- ^

- ^

The economist William Nordhaus found that inventors or creators of technology capture only about 2% of the economic value created by their technology, with the remaining 98% flowing to society as social surplus. Meaning that even though someone gets filthy rich from the thing they invent or create, society at large gets even richer. Interestingly, this has a negative impact on the incentive to spend time and money on research/inventions, which is a problem for economic growth. That’s where patents and IP protection are important for innovation (although this too is abused sometimes).

- ^

Technically, more people means more working-age people (increased labor) and more people working on innovative research or startups. With more people, the chance that there are more brilliant/high-IQ people increases, too. A larger population also increases the “network effects” of ideas as there’s more opportunity for ideas to intermingle with other ideas, all of which can give rise to new ideas.

There’s, however, the additional issue that ideas might be getting harder to find because we’ve picked a lot of the “low-hanging fruit” over the past 1-2 centuries. It’s unclear exactly how this impacts TFP growth, the relationship with population growth, and what we can ultimately do about it.

- ^

Read the text in this picture and consider how bad your intuition is at grappling with exponential growth (at least, I know I am):

- ^

Fossil fuels are an incredibly versatile form of energy, so it’s not straightforward or even obvious that we can completely phase out or replace fossil fuels across our whole economy. In the near to mid-term, we can achieve net zero emissions by capturing carbon emissions from power plants or from the atmosphere (so-called sequestration). Over the long run, fossil fuel reserves will likely become so scarce that they must be replaced somehow. Luckily, there are already ways to make synthetic fuels using carbon from the atmosphere.

Marvelous article! Correlates with my readings in Pinker, Rosling, and the authors (sorry, I don’t have their names, but they have done their homework) of the book “Superabundance.”

Bravo!

I don’t think I have a single criticism...paradigm changing writing. And I have indeed have had a paradigm change over the last few decades, from “Club of Rome “Limits to Growth” and Paul Erlich to graduate to the Abundance mentality of Pinker, Diamandes, and Hans Rosling.

This channel is doing important work in my opinion, as even most progressives and intellectuals are leery of growth as a virtue.

Rudi Hoffman

Port Orange, FL, multiverse.

Thank you for the comment and words of encouragement. The work the progress studies movement is doing is important and something a lot more people need to hear and internalize