A quasi-monthly feature (I skipped it last month, so this is a double portion).

This is a longish post covering many topics; feel free to skim and skip around. Recent blog posts and news stories are generally omitted; you can find them in my links digests.

These updates are less focused than my typical essays; do you find them valuable? Email me or comment (below) with feedback.

Books (mostly)

Books I finished

Thomas Ashton, The Industrial Revolution, 1760-1830 (1948). A classic in the field. I wrote up my highlights here.

Samuel Butler, Erewhon (1872). It is best known for its warning that machines will out-evolve humans, but rather than dystopian sci-fi, it’s actually political satire. His commentary on the universities is amazingly not dated at all, here’s a taste:

When I talked about originality and genius to some gentlemen whom I met at a supper party given by Mr. Thims in my honour, and said that original thought ought to be encouraged, I had to eat my words at once. Their view evidently was that genius was like offences—needs must that it come, but woe unto that man through whom it comes. A man’s business, they hold, is to think as his neighbours do, for Heaven help him if he thinks good what they count bad. And really it is hard to see how the Erewhonian theory differs from our own, for the word “idiot” only means a person who forms his opinions for himself.

The venerable Professor of Worldly Wisdom, a man verging on eighty but still hale, spoke to me very seriously on this subject in consequence of the few words that I had imprudently let fall in defence of genius. He was one of those who carried most weight in the university, and had the reputation of having done more perhaps than any other living man to suppress any kind of originality.

“It is not our business,” he said, “to help students to think for themselves. Surely this is the very last thing which one who wishes them well should encourage them to do. Our duty is to ensure that they shall think as we do, or at any rate, as we hold it expedient to say we do.” In some respects, however, he was thought to hold somewhat radical opinions, for he was President of the Society for the Suppression of Useless Knowledge, and for the Completer Obliteration of the Past.

It’s unclear to me whether the more well-known part about machines evolving is a commentary on technology, or on Darwinism (which was quite new at the time)—but it is remarkable in its logic, and I’ll have to find time to summarize/excerpt it here. See also this article in The Atlantic: “Erewhon: The 1872 Fantasy Novel That Anticipated Thomas Nagel’s Problems With Darwinism Today” (2013).

Agriculture

I’ve been researching agriculture for my book. Mostly this month I have been concentrating on pre-industrial agricultural systems, and the story of soil fertility.

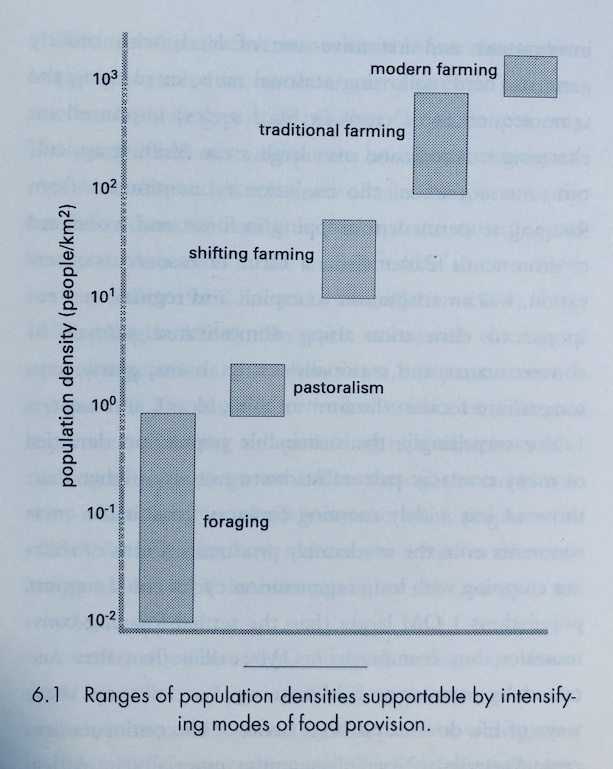

A classic I just discovered is Ester Boserup, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure (1965). Primitive agricultural systems are profligate with land: slash-and-burn agriculture uses a field for a couple of years, then leaves it fallow for decades; in total it requires a large land area per person. Modern, intensive agriculture gets much higher yields from the land and crops it every single year. And there is a whole spectrum of systems in between.

Boserup’s thesis is that people move from more extensive to more intensive cultivation when forced to by population pressure. That is, when population density rises, and competition for land heats up, then people shift towards more intensive agriculture that crops the land more frequently. Notably, this is more work: to crop more frequently and still maintain yields requires more preparation of the soil, more weeding, at a certain level it requires the application of manure, etc. So people prefer the more “primitive” systems when they have the luxury of using lots of land, and will even revert to such systems if population decreases.

Boserup has often been contrasted with Malthus: the Malthusian model says that improvements in agriculture allow increases in population; the Boserupian model is that increases in population drive a move to more efficient agriculture. (See also this review of Boserup by the Economic History Association.)

Vaclav Smil has also been very helpful, especially because he quantifies everything. Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production (2001) is exactly what it says on the tin; Energy in Nature and Society: General Energetics of Complex Systems (2007) is much broader but has a relevant chapter or two. Here’s a chart:

Some overviews I’ve been reading or re-reading:

Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart, A History of World Agriculture: From the Neolithic Age to the Current Crisis (1997)

D. B. Grigg, The Agricultural Systems of the World: An Evolutionary Approach (1974)

Norman S. B. Gras, A History of Agriculture in Europe and America (1940)

For a detailed description of shifting cultivation and slash-and-burn techniques, see R. F. Watters, “The Nature of Shifting Cultivation: A Review of Recent Research” (1960).

A few classic papers on my list but not yet read:

F. M. L. Thompson, “The Second Agricultural Revolution, 1815-1880” (1968)

G. P. H. Chorley, “The Agricultural Revolution in Northern Europe, 1750–1880: Nitrogen, Legumes, and Crop Productivity” (1981)

Finally, I’ve perused Alex Langlands, Henry Stephens’s Book of the Farm (2011), an edited edition of a mid-19th century practical guide to farming. Tons of details like exactly how to store your turnips in the field, to feed your sheep (basically make a triangular pile on the ground, and cover them with straw):

History of fire safety

I read several chapters of Harry Chase Brearley, Symbol of Safety: an Interpretative Study of a Notable Institution (1923), a history of Underwriters Labs. UL was created over 100 years ago by fire insurance companies in order to do research in fire safety and to test and certify products. They are still a (the?) top name in safety certification of electronics and other products; their listing mark probably appears on several items in your home (it only took me a few minutes to find one, my paper shredder):

Brearley also wrote The History of the National Board of Fire Underwriters: Fifty Years of a Civilizing Force (1959), which I haven’t read yet. A more modern source on fire safety is Bruce Hensler, Crucible of Fire: Nineteenth-Century Urban Fires and the Making of the Modern Fire Service (2011). Hensler, a former firefighter himself, also writes an interesting history column for an online trade publication.

Overall, the story of fire safety seems like an excellent case study in one of my pet themes: the unreasonable effectiveness of insurance as a mechanism to drive cost-effective safety improvements. See my essay on factory safety for an example.

Classics in economics/politics

I have sampled, but have not been in the mood to get far into:

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942)

David Landes, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present (1969)

Gregory Clark, A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World (2007)

I’m sure I will come back to all of these at some point.

Other random books I have started

Jerry Pournelle, Another Step Farther Out: Jerry Pournelle’s Final Essays on Taking to the Stars (2007). Pournelle is a very well-known sci-fi author (Lucifer’s Hammer, The Mote in God’s Eye, etc.) This is a collection of non-fiction essays that he wrote over many years, mostly about space travel and exploration. He would have been at home in the progress movement today.

Iain M. Banks, Consider Phlebas (1987), the first novel in the “Culture” series. It’s been recommended to me enough times, especially in the context of AI, that I had to check it out. I’m only a few chapters in.

Articles

Historical sources

Annie Besant, “White Slavery in London” (1888). Besant was a British socialist and reformer who campaigned for a variety of causes from labor conditions to Indian independence. In this article, she criticizes the working conditions of the employees at the Bryant and May match factory, mostly young women and girls. Among other things, the workers were subject to cruel and arbitrary “fines” docked from their pay:

One girl was fined 1s. for letting the web twist round a machine in the endeavor to save her fingers from being cut, and was sharply told to take care of the machine, “never mind your fingers”. Another, who carried out the instructions and lost a finger thereby, was left unsupported while she was helpless.

Notably missing from Besant’s list of grievances is the fact that the white phosphorus the matches were made from caused necrosis of the jaw (“phossy jaw”). However, the letter ultimately precipitated a strike, which won the girls improved conditions, including a separate room for meals so that food would not be contaminated with phosphorus. White phosphorus was eventually banned in the early 20th century. (I mentioned this story in my essay on adapting to change, in which I contrasted it with radium paint, another occupational hazard.) See also Louise Raw, Striking a Light: The Bryant and May Matchwomen and their Place in History (2009).

Admiral Hyman Rickover, the “Paper Reactor” memo (1953):

An academic reactor or reactor plant almost always has the following basic characteristics: 1. It is simple. 2. It is small. 3. It is cheap. 4. It is light. 5. It can be built very quickly. 6. It is very flexible in purpose (“omnibus reactor”) 7. Very little development is required. It will use mostly “off-the-shelf” components. 8. The reactor is in the study phase. It is not being built now.

On the other hand, a practical reactor plant can be distinguished by the following characteristics: 1. It is being built now. 2. It is behind schedule. 3. It is requiring an immense amount of development on apparently trivial items. Corrosion, in particular, is a problem. 4. It is very expensive. 5. It takes a long time to build because of the engineering development problems. 6. It is large. 7. It is heavy. 8. It is complicated. …

The academic-reactor designer is a dilettante. He has not had to assume any real responsibility in connection with his projects. He is free to luxuriate in elegant ideas, the practical shortcomings of which can be relegated to the category of “mere technical details.” The practical-reactor designer must live with these same technical details. Although recalcitrant and awkward, they must be solved and cannot be put off until tomorrow. Their solutions require man power, time, and money.

Russell Kirk, “The Mechanical Jacobin” (1962). Kirk was a mid-20th century American conservative, and not a fan of progress. In this brief letter he calls the automobile “a mechanical Jacobin—that is, a revolutionary the more powerful for being insensate. From courting customs to public architecture, the automobile tears the old order apart.”

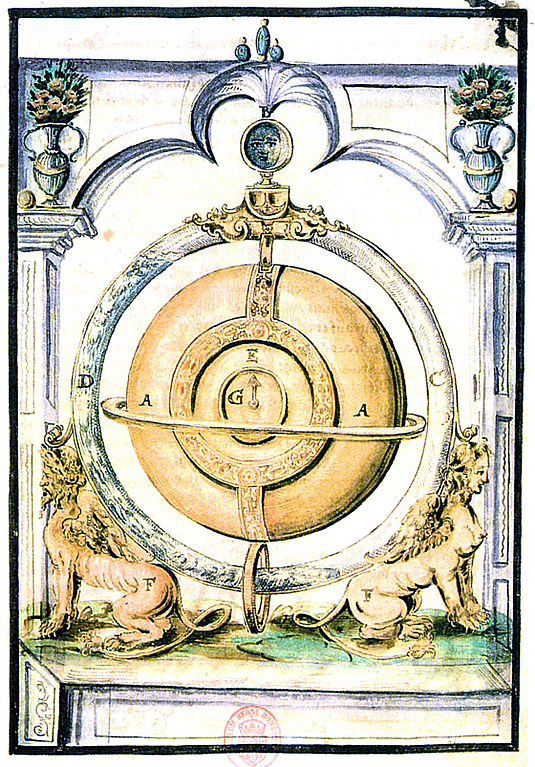

Jindřich Michal Hýzrle, “Years 1607. Notes of a journey to the Upper Empire, to Lutrink, to Frankreich, to Engeland and to the Nýdrlatsk provinces, aged 32” (1614). In Czech but the Google Translate plugin does a decent job with it. Notable because it contains an account of Cornelis Drebbel presenting his famous “perpetual motion” clockwork device to King James of England. The king is reported to have replied:

Friends, you lecture and say great things, but not so that I have such great knowledge and revelations to laugh at. Otherwise I wonder that the Lord God has hidden such things from the beginning of the world from so many learned, pious and noble people, preserved them for you and only in this was already the last age to reveal it. However, I will try it once and I will find your speech to be true, that there is no trickery, charms and scheming in it, you and all of you will have a decent reward from me.

Evidently Drebbel’s “decent reward” was a position as court engineer.

Scientific American, “Septic Skirts” (1900). A letter to the editor, reproduced here in full:

The streets of our great cities are not kept as clean as they should be, and probably they will not be kept scrupulously clean until automobiles have entirely replaced horse-drawn vehicles. The pavement is also subjected to pollution in many ways, as from expectoration, etc. Enough has been said to indicate the source and nature of some of the most prevalent of nuisances of the streets and pavements, and it will be generally admitted that under the present conditions of life a certain amount of such pollution must exist, but it does not necessarily follow that this shall be brought indoors. At the present time a large number of women sweep through the streets with their skirts and bring with them, wherever they go, the abominable filth which they have taken up, which is by courtesy called “dust.” Various devices have been tried to keep dresses from dragging, but most of them have been unsuccessful. The management of a long gown is a difficult matter, and the habit has arisen of seizing the upper part of the skirt and holding it in a bunch. This practice can be commended neither from a physiological nor from an artistic point of view. Fortunately, the short skirt is coming into fashion, and the medical journals especially commend the sensible walking gown which is now being quite generally adopted. These skirts will prevent the importation into private houses of pathogenic microbes.

See also my essay on sanitation improvements that reduced infectious disease.

AI risk

I did a bunch of research for my essay on power-seeking AI. The paper that introduced this concept was Stephen M. Omohundro, “The Basic AI Drives” (2008):

Surely no harm could come from building a chess-playing robot, could it? In this paper we argue that such a robot will indeed be dangerous unless it is designed very carefully. Without special precautions, it will resist being turned off, will try to break into other machines and make copies of itself, and will try to acquire resources without regard for anyone else’s safety. These potentially harmful behaviors will occur not because they were programmed in at the start, but because of the intrinsic nature of goal driven systems.

This was followed by Nick Bostrom, “The Superintelligent Will: Motivation And Instrumental Rationality In Advanced Artificial Agents” (2012), which introduced two key ideas:

The first, the orthogonality thesis, holds (with some caveats) that intelligence and final goals (purposes) are orthogonal axes along which possible artificial intellects can freely vary—more or less any level of intelligence could be combined with more or less any final goal. The second, the instrumental convergence thesis, holds that as long as they possess a sufficient level of intelligence, agents having any of a wide range of final goals will pursue similar intermediary goals because they have instrumental reasons to do so.

Then, in “Five theses, two lemmas, and a couple of strategic implications” (2013), Eliezer Yudkowsky added the ideas of “intelligence explosion,” “complexity of value” (it’s hard to describe human values to an AI), and “fragility of value” (getting human values even a little bit wrong could be very very bad). From this he concluded that “friendly AI” is going to be very hard to build. See also from around this time Carl Shulman, “Omohundro’s ‘Basic AI Drives’ and Catastrophic Risks” (2010).

One of the best summaries of the argument for existential risk from AI is Joseph Carlsmith, “Is Power-Seeking AI an Existential Risk?” (2021), which is also available in a shorter version or as a talk with video and transcript.

A writer I’ve appreciated on AI is Jacob Steinhardt. I find him neither blithely dismissive nor breathlessly credulous on issues of AI risk. From “Complex Systems are Hard to Control” (2023):

Since building [powerful deep learning systems such as ChatGPT] is an engineering challenge, it is tempting to think of the safety of these systems primarily through a traditional engineering lens, focusing on reliability, modularity, redundancy, and reducing the long tail of failures.

While engineering is a useful lens, it misses an important part of the picture: deep neural networks are complex adaptive systems, which raises new control difficulties that are not addressed by the standard engineering ideas of reliability, modularity, and redundancy.

And from “Emergent Deception and Emergent Optimization” (2023):

… emergent risks, rather than being an abstract concern, can be concretely predicted in at least some cases. In particular, it seems reasonably likely (I’d assign >50% probability) that both emergent deception and emergent optimization will lead to reward hacking in future models. To contend with this, we should be on the lookout for deception and planning in models today, as well as pursuing fixes such as making language models more honest (focusing on situations where human annotators can’t verify the answer) and better understanding learned optimizers. Aside from this, we should be thinking about other possible emergent risks beyond deception and optimization.

Stuart Russell says that to make AI safer, we shouldn’t give it goals directly. Instead, we should program it such that (1) its goals are to satisfy our goals, and (2) it has some uncertainty about what our goals are exactly. This kind of AI knows that it might make mistakes, and so it is attentive to human feedback and will even allow itself to be stopped or shut down—after all, if we’re trying to stop it, that’s evidence to the AI that it got our preferences wrong, so it should want to let us stop it. The idea is that this would solve the problems of “instrumental convergence”: an AI like this would not try to overpower us or deceive us.

Most people who work on AI risk/safety are not impressed with this plan, for reasons I still don’t fully understand. Some relevant articles to understand the arguments here:

Paul Christiano, “The easy goal inference problem is still hard” (2015)

Scott Alexander, “CHAI, Assistance Games, And Fully-Updated Deference” (2022)

Ivan Vendrov, “Updated Deference is not a strong argument against the utility uncertainty approach to alignment” (2022)

Finally, various relevant pages from the AI safety wiki Arbital:

Other random articles

Bret Devereaux, “Why No Roman Industrial Revolution?” (2022). I briefly summarized this and responded to it here.

Alex Tabarrok, “Why the New Pollution Literature is Credible” (2021). On one level, this is about the health hazards of air pollution. More importantly, though, it’s about practical epistemology: specifically, how much credibility to give to research results.

Casey Handmer, “There are no known commodity resources in space that could be sold on Earth” (2019):

On Earth, bulk cargo costs are something like $0.10/kg to move raw materials or shipping containers almost anywhere with infrastructure. Launch costs are more like $2000/kg to LEO, and $10,000/kg from LEO back to Earth.

What costs more than $10,000/kg? Mostly rare radioactive isotopes, and drugs—nothing that (1) can be found in space and (2) has potential for a large market on Earth.

And continuing the industry-in-space theme: Corin Wagen, “Crystallization in Microgravity” (2023). A technical explainer of what Varda is doing and whether it’s valuable:

Varda is not actually ‘making drugs in orbit’ …. Varda’s proposal is actually much more specific: they aim to crystallize active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs, i.e. finished drug molecules) in microgravity, allowing them to access crystal forms and particle size distributions which can’t be made under terrestrial conditions.

Arthur Miller, “Before Air-Conditioning” (1998). A brief portrait.

Kevin Kelly, “The Shirky Principle” (2010). “Institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution.”

Interesting books I haven’t had time to start

The most intriguing item sitting on my desk right now is William L. Thomas, Jr. (editor), Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth (1956), the proceedings of a symposium by the same name that included Lewis Mumford (who became one of the most influential technology critics of the counterculture). In particular, I’m interested to understand how early agriculture (see above) created mass deforestation.

Other books on my reading list include:

Economic and technology history:

Col. Norman Beasley, Knudsen: A Biography (1947). “The tale of the immigrant bicycle mechanic who revolutionized American industry and buried the Axis powers with mass production.” Via Brian Potter here and here

Thomas Almeroth-Williams, City of Beasts: How Animals Shaped Georgian London (2019)

Joseph and Frances Gies, Cathedral, Forge and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Ages (1995)

William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991)

Michael Webber, Power Trip: The Story of Energy (2019)

History of disease:

Eric Lax, The Mold in Dr. Florey’s Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle (2004)

Kyle Harper, Plagues upon the Earth: Disease and the Course of Human History (2021)

Intellectual and cultural history:

Charles Freeman, The Reopening of the Western Mind: The Resurgence of Intellectual Life from the End of Antiquity to the Dawn of the Enlightenment (2023)

Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (2003)

Financial history:

Milton Friedman, Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History (1992)

Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World (2008)

Edward Chancellor, The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest (2022)

Political history:

Jonathan Healey, The Blazing World: A New History of Revolutionary England, 1603-1689 (2023)

Christopher Clark, Revolutionary Spring: Europe Aflame and the Fight for a New World, 1848-1849 (2023)

Other:

Robert Zubrin, The Case For Nukes: How We Can Beat Global Warming and Create a Free, Open, and Magnificent Future (2023)

Seth Siegel, Let There Be Water: Israel’s Solution for a Water-Starved World (2015)

Jack Farchy and Javier Blas, The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources (2021)

Jennifer Pahlka, Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better (2023)

Thanks for sharing the “the unreasonable effectiveness of insurance” books and pieces about fire safety. This is also a theme that fascinates me, and while I was working in reinsurance modeling for cybersecurity I became fascinated with the history of steam boilers. This technological innovation is a great case study for progress that creates problems that requires more progress to solve.

The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (now a part of MunichRe) was created to address this problem and the blog post below describes why the sinking of the Sultana steam ship in 1865 was a critical turning point: https://blog.hsb.com/2015/03/30/sultana/

I believe this precedent setting case predates the UL by about 30 years and well before the commercialization of electricity (besides nascent telegraph systems). Prior to the HSB Inspection and Insurance Company, insurance was limited to covering mostly natural causes of marine/storm (ancient) and property/fire (Stuart Era) losses. There was risk of piracy, so some of the losses were man-made, but prior to the Industrial Revolution technological risk was solved by lack of progress.

Fascinating, thanks for the pointer!