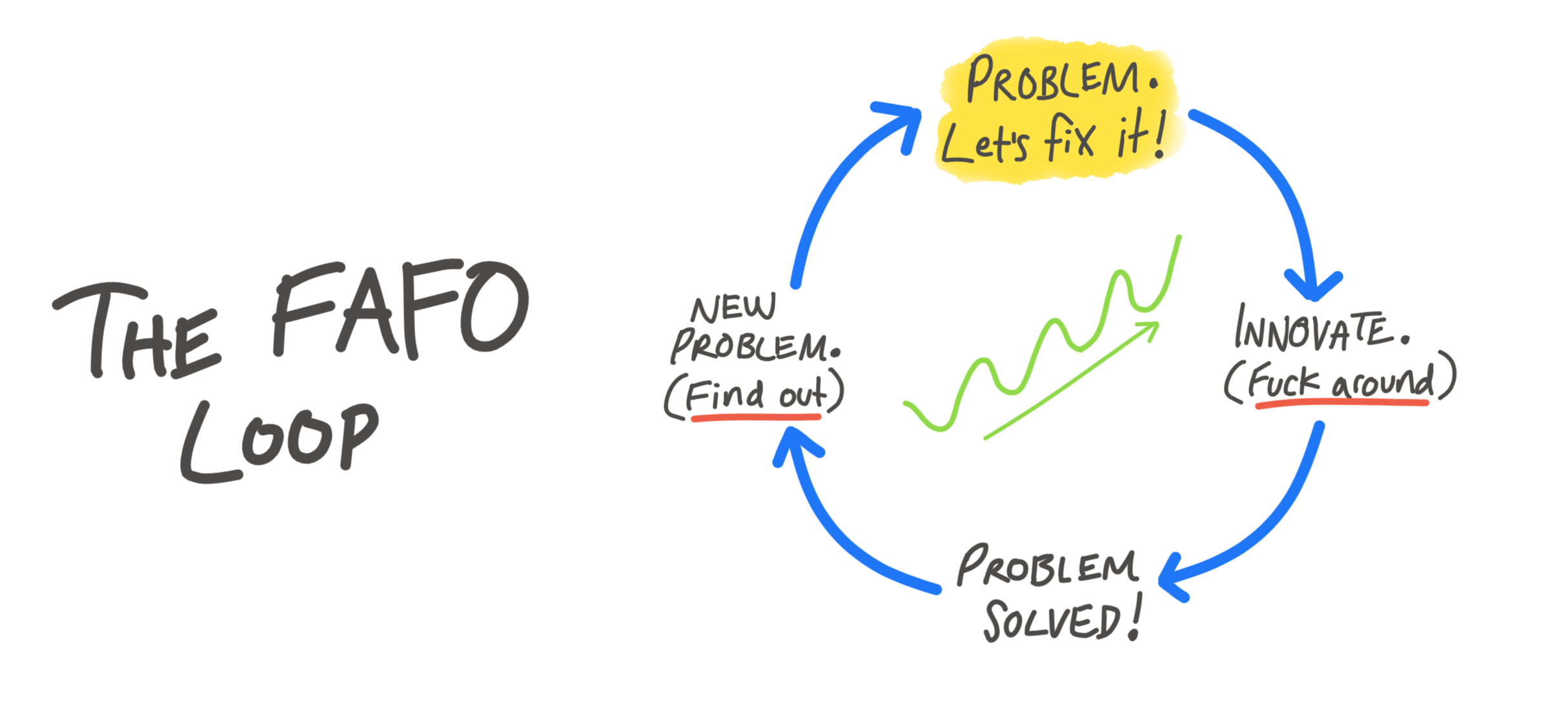

The history of humanity can be summarized as a long series of “fuck around and find out.”[1]

It’s the cycle of innovation and consequence. We see a problem X, we invent a solution, we discover that solution creates a new problem, we can’t stop doing X, and we have to invent another solution. And so on. This is our philosophy: to seek, to solve, to stumble anew.

We invented fire, which kept us warm and cooked our food, and also burned down our villages and killed us in wildfires. We invented knives and arrows and saws, which helped us hunt and build, and also cut off our fingers and stabbed us in the gut. We invented agriculture, providing food surplus, yet it sowed seeds of war, famine, and environmental decay. We invented writing, which allowed us to communicate and record history, and also spread lies and misinformation. We invented steam power, which increased productivity and transportation, and also polluted our air and crushed our limbs in factories. We invented smartphones, and… well, I won’t go there.

It’s the basic arc of human history. Progress is driven by unintended consequences. But can we manage these risks?

Pro-action

The Precautionary Principle says we shouldn’t pursue any action or policy that might cause significant harm unless we’re nearly certain it’s safe. It puts the burden of proof on the inventor to prove the invention is not harmful.

Had we always used this approach though, most invention would never have occurred.

A better approach is the Proactionary Principle.

The Proactionary Principle is based on the observation that the most valuable innovations are often not obvious, and we don’t understand them until after they’ve been invented. It says we need to weigh the opportunity cost of restrictive measures against the potential damages of new technologies.

Kevin Kelly expands on this more in the book “What Technology Wants”:

Anticipation. The more techniques we use, the better, because different techniques fit different technologies. Scenarios, forecasts, and outright science fiction give partial pictures, which is the best we can expect. Anticipation should not be judgment—the purpose is preparation not accuracy.

Continual assessment. We have increasing means to quantifiably test everything we use all the time, not just once.

Prioritization of risks, including natural ones. Risks are real but endless. Not all risks are equal. They must be weighted and prioritized.

Rapid correction of harm. When things go wrong things should be remedied quickly. Rapid restitution for harm done would also indirectly aid the adoption of future technologies. But restitution should be fair (no hypothetical harm or potential harm).

Not prohibition by redirection. Banishment of dubious tech does not work. Instead, find them new jobs. A technology can play different roles in society. It can have more than one expression. It may take many tries, many jobs, and many mistakes before a fit is made. Prohibiting them only drives them underground, where their worst traits are brought out.

Let me repeat this line: “Not all risks are equal.”

This is the key. Nassim Taleb talks about risk of ruin, and he argues the Precautionary Principle should only apply when systemic, extinction-level risks are possible. I tend to agree, though it can be a hard balance.

The risk of ruin matters because the cost is complete destruction of humanity or life on Earth. These are the cases where applying the Precautionary Principle makes sense.

Even so, in areas like bioengineering and AI it’s too easy to conjure hypothetical, catastrophic scenarios. Engineered pandemics. Superintelligent paperclip-maximizer AIs. All sorts of bad things can happen! And none of them are impossible. These are the scenarios Taleb is talking about — but we need to weigh them appropriately. Our primitive monkey brains are good at over-estimating very unlikely risks.[2]

Find out

The path of progress has always been to venture into the unknown, make mistakes, and find out.

We’ve found out how to make fire, build cities, cure diseases, split the atom, land on the moon, turn sand into intelligence, and edit genes. We’ve found out how to make weapons of mass destruction, how to pollute the environment, how to exploit and oppress each other. We’ve also found out how to prevent wars, protect the environment, and promote human rights.

The Proactionary Principle is not just a guide; it’s a belief in action over inaction, in knowledge over ignorance, in growth over stagnation, in hope over fear.

Let’s choose to “find out”, and embrace the future unknowns. Because, let’s face it… we’re still going to fuck around and find out anyway.

- ^

FAFO is originally a biker acronym for “Fuck Around and Find Out”. The American Dialect Society chose it as their word of the year for 2022!

- ^

This reminds me of the Anxiety character in Pixar’s recent movie “Inside Out 2”: “A bundle of frazzled energy, Anxiety enthusiastically ensures Riley’s prepared for every possible negative outcome.” SPOILER ALERT: When Anxiety takes over, relationships and quality of life suffer. In the end, the emotions are balanced and Anxiety is helpful to prepare for the future, but should never be in charge.

I think this is presupposing the question isn’t it.

If a risk is indeed very unlikely, then we will tend to overestimate it. (If the probability is 0 it’s impossible to underestimate)

But for risks that are actually quite likely, then we are more likely to underestimate them.

And of course, bias estimates cut both ways. “Our primitive monkey brains are good at ignoring and underestimating abstract and hard to understand risks”.